- Home

- Sarfraz Manzoor

Greetings from Bury Park Page 7

Greetings from Bury Park Read online

Page 7

My mother would ask me to talk to Sohail. ‘Ask him what he is doing with his life. Is it any sort of life? Dressing like a tramp and not speaking to his own parents?’

What my parents did not know was that Sohail was planning to leave Britain. His friend Zahid had spent the summer in the United States and had returned full of stories about how amazing it was and how the two of them should try and get work. Frustrated by the lack of decent work in Luton and with tension running high in the family, my brother agreed, and in the summer of 1989 he told my father he was leaving for the United States and he did not know when he would be back. The plan was to travel to New York and take a hired car down to Florida where Sohail and Zahid had a friend who would help them find work. My brother had bought a one-way plane ticket; bored at home, he wanted excitement and there was nothing keeping him in Luton.

The only time I ever saw my father cry was on the day Sohail left home to take the coach to Heathrow. Even after he had shouted at him and told him he had ruined his life my father still reached over to hug Sohail. His eyes were shiny with tears. Sohail was leaving and we did not know when we would hear from him again.

It was in the early hours of the morning, four days after Sohail had left. The telephone would not stop ringing. Shaking the sleep out of my head, I picked up the phone. It was Sohail and he wanted to speak to my father. I went upstairs but by now the whole family were awake. My mother and Uzma joined me on the sofa in the living room as my father talked to my brother. Sohail and Zahid had arrived in New York and were driving from Myrtle Beach to Charleston, North Carolina, in two hired cars when Zahid was involved in a car crash. My brother’s closest friend had died in his arms on a highway four thousand miles from home. I knew Zahid; he was always smiling, positive and full of life. I broke down in tears. My father rang Zahid’s family to make preparations to bring the body home for a Muslim burial. Sohail returned home.

While I was away at university Sohail finally agreed to visit Pakistan and find a bride. In 1993, the whole family – except Navela – went to Pakistan for his wedding.

I had to be persuaded to attend. It was not that I didn’t want to go to the wedding itself but rather that I didn’t want to go to Pakistan. I eventually agreed on the condition that I only spent a week there.

I have very few recollections from the trip. Each day was a flurry of meeting cousins and aunts and uncles. What I remember most clearly was a conversation where I was talking to some of my cousins and they were telling me how appalling England was. I sat sipping tea as they denounced England as being the home of sin and decadence and amorality. I could not be bothered to disagree or argue with them and so sat in silence. Finally they stopped talking. The room was quiet. ‘So tell me,’ piped up one of the cousins, a portly man with a large belly and full moustache, ‘could you help me get to England?’

Sohail was to marry Nazia, a girl who grew up in the same village as us and who was distantly related. I remembered seeing her the last time I was in Pakistan; it was hard to forget her as she was the only Pakistani girl I had met with green eyes. She was only twelve back then but now she was eighteen.

The night before the wedding we slept in our uncle’s house. There were two rope beds in the room, Sohail lay in one and I in the other. Neither of us could sleep. I don’t remember much of what I said to my brother that night but I do remember the sense of feeling deeply connected to him. It was his last night as a single man, tomorrow his life would be changed for ever. We both knew Sohail’s relationship with the rest of the family would never be the same. If our family had been one where brothers spoke openly and honestly about their feelings, I might have enquired whether he was excited or scared about getting married, I might have told him I was pleased that I was there to see his marriage. As it was I asked him if he was all right and he told me he was.

On his wedding day my brother was clean-shaven and dressed in a charcoal suit with a rose in his lapel. Nazia wore a blood-red wedding dress and was almost invisible under a mountain of gold jewellery. I was the official photographer and was busy snapping the bride and groom from every angle. The ceremony was in the main room of the InterContinental Hotel in Lahore, Sohail and Nazia were seated at the front, facing scores of relatives. My father and mother were standing, watching the proceedings. My father had a grave expression on his face, he looked stressed. My mother wore gold earrings, a necklace, bangles and lipstick, and was smiling. I looked across at the relatives who were all chatting and laughing and listening to the wedding songs being played on the public address system. I thought these are my relatives, I am part of them and they are part of me. Some even looked like me. I could lie and say I was different, that I had nothing in common with these people except the colour of our skin, and yet the truth was there in the shape of our noses and the fleshiness of our earlobes. In that instant I felt a sense of connection, a sense of being part of something bigger than my direct family that I had not felt before.

* * *

Uzma and I returned to England shortly after the wedding but the rest of the family remained for another week. When they returned, Sohail and Nazia moved into my parents’ home. By then, I had graduated from university but was still living in Manchester. I had assumed that since my brother had relented and agreed to an arranged marriage my parents would be pleased with him. When I rang home however, Uzma would report about the tensions back in Luton and how my parents were barely on speaking terms with Sohail. I did not understand what the cause of the trouble was, Sohail had not disgraced the family, his wife was from the same village as my mother. Despite that, my father was not happy. His daughter had let him down and somehow so had his eldest son. When my brother dressed in tracksuit bottoms and went unshaven and dishevelled, my father believed he was insulting his good name. My father’s life had been driven by self-improvement and he had assumed that his children would continue that journey. His anger towards Sohail was born of the frustration that his eldest son was not only failing to make progress but also actively undermining all his hard work. ‘The worst mistake I ever made was to come to Britain,’ my father would claim. ‘I came to this country thinking I was doing the right thing. I did not know I would end up losing my own children. Too much freedom in this society. The parents do their best for their children but at the end the children turn round and say, ‘‘Who are you?’’’

Sohail was planning on leaving my parents’ home and buying his own house but the death of my father thrust him unexpectedly into the unwanted position as head of our family. My mother, who with my father had attacked and criticised him, was now reliant on him. I could only be thankful that it was him and not me.

Three months after my father’s death I was back in Manchester and the responsibility of maintaining the household fell entirely on my brother’s shoulders. He was working in a factory but he knew he needed to find a way to make more money. While I had always protested that money meant little to me, my brother did not have a choice. Through fearlessness and hard work he established his own property business and he used the money to take the family out of Marsh Farm. He bought two houses on a nice street in a smart part of Luton; he lived in one with his wife, and my mother and sister lived in the other.

He made sure that I was aware of his contribution. ‘The only reason you can do what you do is because I do what I do,’ he would tell me. ‘You don’t have to worry about Mum and see that the bills are paid. I’m the one who does that, you’re the one travelling the world to see Bruce Springsteen.’ Like my father Sohail saw success only in financial terms. ‘The money you’re making is peanuts, how are you going to plan for your future on that? You know that Mum complains you don’t ever talk to her – she says you come home, eat her food and then as soon as your Sikh friend calls you, you’re out of the door until God knows when. Is that a way to treat your own mother?’

‘But what am I meant to say to her?’ I would protest.

‘She’s our mother, and it’s my job to tell you what she says

to me. She thinks you’re too proud to talk to her. That’s what she says. She says that you have forgotten how to talk to your own family. You don’t have anything left to say to us.’

I listened and said nothing.

* * *

It was the first week of 2004 and I was in Luton spending New Year with my family. I had been living in London for some time by now. I was stretched out on the sofa watching a Pakistani drama serial with my mother who was sitting in an armchair. ‘Do you want a mug of tea, son?’ she asked me.

I nodded. As she rose from her seat my mother suddenly fell back into the chair. ‘What happened?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know, I just felt a stab of pain. It’s gone now,’ she replied.

Once she had returned from the kitchen my mother began to complain of pins and needles in her feet. She complained that she was feeling feverish, and when she tried to stand up her body failed to hold her weight. It was Sunday evening. Uzma suggested taking her upstairs to her bedroom. We both helped her upstairs.

I rang my brother to tell him what was going on. Sohail didn’t think it was anything serious and said to keep an eye on her. He would take her to see the doctor in the morning. Meanwhile, my mother was now saying she had lost some feeling on one side of her body. This seemed worrying so I went on the internet and began searching for what the problem might be; I had a suspicion it was a stroke, and once I began reading about the tell-tale signs I became convinced of it. I rang the night doctor who arrived in the early hours of the morning, took her temperature and her pulse and said that she was suffering from complications relating to high blood pressure. I didn’t believe him and told him I was concerned she might have had a stroke. He told me I was mistaken. Without expert knowledge I was unable to argue on the specifics and reluctantly allowed him to leave.

The next morning I awoke and found my mother weeping with pain; I rang my brother who drove us to the emergency ward at Luton and Dunstable Hospital. An Indian doctor examined her and confirmed she had suffered a stroke. He took us into another room and told Sohail and me that it was too early to know how serious the stroke had been. This would require a CAT scan, which was not possible until the following day. In the meantime there was no way of knowing her chances of survival. I asked the doctor what the worst case scenario was.

‘It’s possible that bleeding is occurring in the brain,’ he told me, ‘so it is possible she might not survive the day. In the case of a brain haemorrhage there is really very little we can do.’

The doctor departed and Sohail and I were left trying to absorb what he had told us. We both returned to our mother who was lying on a hospital bed in the emergency ward with pale-green curtains dividing us from the other patients. ‘The doctor has said they’re going to do some more tests to find out what’s going on,’ my brother said quietly, ‘and until then they can’t tell us what’s happening.’

I didn’t say anything. I just kept looking hard into my mother’s face, studying the lined forehead and worried eyes, and wondering whether she would be alive by the end of the day.

The CAT scan revealed that there was not a clot on the brain but the impact of the stroke had left my mother unable to move one side of her body. She could not walk or eat solid food, and when she spoke she slurred her words distressingly. The hospital kept her in the ward for two weeks and during that time there was hardly a minute that she was not with one of her family. I took leave from work and shared the time at her side with Uzma and my brother. The ward she was in was for the elderly; the woman in the bed opposite was in her nineties and spent the two weeks unconscious, another woman was suffering from pneumonia and kept pleading with the nurses to call her daughter to ask her to visit. My mother was the only woman in the ward whose children spent all day with her.

When I had called Navela to tell her that our mother was ill she had driven to the hospital and brought her children. By now, she had four of them. I hadn’t asked Sohail or my mother whether I should call Navela, it just seemed the right thing to do. When she turned up unannounced with her children in tow, my mother burst into tears. Uzma and I left them together, both crying uncontrollably as Navela’s children looked on in bafflement. Navela sat with our mother for two hours talking about the children and Shaukat. She said that she was happy and she missed her, and that she often thought of calling but each time she backed off, worried at the reception she would receive. When it was time to leave, Navela gave our mother a hug and promised she would be back. She did not return.

* * *

Gradually over the two weeks my mother was in hospital, she was able to start walking very slowly as long as she had someone to hold on to. Her walk was unsteady and when we watched her it was as if she might falter and fall at any stage. But she was making improvements and, with the threat of further strokes receding, the hospital told us she could go back home.

When she returned home initially my mother was unable to walk; the prospect that she would need full-time care was looming. Feeling that she might now be a burden, my mother became very depressed. She was a woman who prided herself on not being reliant on others; if anything, the rest of us still relied on her.

But now my mother needed help with everything: Uzma had to feed her with a small spoon; if she wanted to walk anywhere someone had to be there for her to hold on to; a lady from the council had to come each morning to help her dress and wash herself. For my mother this was an unbearable loss of pride; to have a stranger, and a white woman at that, helping her into a bath was an indignity too far. ‘Would it not have been better if I had joined your father when he left rather than have to become a burden on you?’ she would say. ‘All you children are busy with your own lives. I spent my life looking after you and now that I am in this state who is going to have time to take care of me?’

It was not going to be me. Having taken two weeks off work I returned back to London, leaving Sohail, Nazia and Uzma to care for our mother. Since everyone worked there was no one to keep her company during the day. Having read about aftercare for stroke victims I made enquiries about community groups for elderly Asians. What most depressed my mother was feeling alone during the day; if there was somewhere she could go where she could spend time with other older Pakistani women it might, I hoped, improve her mood and perhaps her health. When we suggested this to my mother she became even more miserable. ‘So this is what I have been reduced to then, is it?’ she said. ‘A problem for the rest of you. Someone to throw out of the house like a dog?’

‘I’m trying to find a place where you can go to meet other people like you,’ I would reply. ‘We’re not trying to throw you out, it might be nice to go somewhere different, that’s all.’

‘That’s the problem, son. Your daddy has gone somewhere and you know my only wish is that he could have taken me with him. Then I would not have to endure this living hell of being a burden to my own children.’

We did not take my mother to a community day centre, not because of her reluctance but because no such place existed. Since Asians are known for their extended families and how they respect their elders, there were no groups in Luton of the type I was seeking for my mother. It was assumed there wouldn’t be a demand.

And so my mother spent the days alone watching Pakistani soaps on satellite television until the others returned from work in the evenings. ‘It’s easy for you, isn’t it, coming home and saying the right words and then leaving,’ Sohail would say to me when I came back to Luton. ‘It’s me who has to be here all the time. What would happen if I suddenly said I didn’t want to do it any more? What would happen if I said now it’s your turn to look after Mum. Why don’t you invite her to spend a week at your place in London? Give the rest of us a break? You don’t think like that, do you, because you’re selfish. You just say what you need to to get everyone off your back and then off you go back to London to live your life.’

It was hard listening to Sohail because he was telling the truth: the rest of my family had paid the price

for my freedom. I had the luxury of being the younger son.

My mother’s health improved and the scare about long-term care lifted; gradually she began to regain the ability to walk and talk. However, one of the most painful consequences of the stroke was that she never regained her sense of taste. My mother, the woman responsible for the most amazing food I had ever eaten, could not taste her own cooking.

I returned to life in London but I knew what was in store for me each time I came home. The usual lectures about responsibility from my brother. As a consequence, my visits to Luton became less frequent and my relationship with Sohail practically non-existent. Sohail and I seemed to have nothing to say to each other; he did not respect what I had achieved in my life and he felt that everything that had been achieved was due to his efforts.

Although I was not speaking to my brother I continued talking to Uzma. My younger sister was working for a brewery company and living with my mother. That had not been the plan; she too had wanted to go to university after college and had been arguing with my father about being allowed to go. Many Asian girls whose parents did allow them to continue their studies did so on the condition that they studied nearby and so could remain at home. But Uzma did not want to study in Luton and had been fighting to be allowed to leave home like both her brothers. She had been having one such argument on the day that my father suffered his heart attack. It was now inconceivable that Uzma would be able to leave home. At the time she was working in the same textile factory that Navela had worked in fifteen years earlier; it was soul-crushing work for someone as intelligent as my sister, but with our father gone financial demands meant she was unable to leave.

Music and fashion were her only escape from the tedium of the real world. Uzma loved Bruce Springsteen almost as much as I did. I had indoctrinated her when I was sixteen and she was twelve, and on each tour I would make sure to take her to a Springsteen concert. Her other great passion was clothes. Uzma would rifle through vintage clothes shops for interesting clothes that she would wear in imaginative ways. While other Asian girls would parade through the Arndale Centre in their identikit uniforms of shalwaar kameez or hijabs, Uzma would be in a fake-fur coat, knee-length boots and nose ring. She would wear green eyeliner and maroon lipstick, she was obsessed with maintaining her inch-long fingernails. During the winter she wore a bright-pink coat and black velvet gloves. It was her way to demonstrate that she too had dreams that stretched beyond Luton. It must have been hard for Uzma when I called to tell her about my holidays and concerts and parties and friends; it was a world that she ached for herself but which she had been denied. Eventually Uzma did manage to leave the textile factory. She became an accounts clerk; new work friends would ask her out for evening meals and she was able to accept. Sohail appeared indifferent to Uzma’s aspirations; she remained an embarrassment because she was unmarried and wore clothes that hinted at a personality.

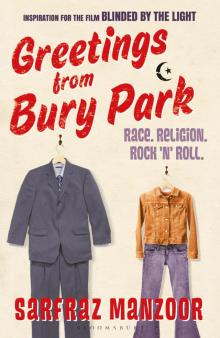

Greetings from Bury Park

Greetings from Bury Park