- Home

- Sarfraz Manzoor

Greetings from Bury Park Page 2

Greetings from Bury Park Read online

Page 2

Mohammed made his way out of Heathrow and hailed a taxi. In his trouser pocket he had a piece of paper with the name and address of his childhood friend Shuja whose brother worked with him in Pakistan. When Shuja had learnt Mohammed was coming to England he had told him he was welcome to live with him. On the piece of paper was an address in Chesham where Shuja lived in a large rented house. Mohammed approached a taxi driver and handed him the piece of paper, pointing at the handwritten address. The taxi driver took the paper and, after reading it, started driving.

The cab arrived at a seven-bedroom house, which already slept thirty-one Pakistanis. Shuja and the others hugged Mohammed and congratulated him for making the journey. It was soon explained to my father that they slept in shifts; some of the men worked nights and others during the day. It was important that the beds were free by the morning as another group of men would be sleeping in them during the daytime.

It was hard for my father to get used to living in England. Everything was different. In Pakistan all meat had been halal but now the nearest halal butcher was twelve miles away. At weekends a man came delivering live chickens; these would be sacrificed and the skin, head and other unused parts would be wrapped in a brown paper bag and thrown into the coal fire.

There was no television where my father lived but there was an old twin-track tape player and in the evenings the men would gather together and listen to old Hindi film songs in the living room. When they were feeling especially homesick they would take a coach to Southall where, on Sunday afternoons, the cinema would play Indian films. The theatre would be full of lonely Asian men who had travelled from across the south-east to see these films.

Meanwhile it was hard for my mother, raising her children without her husband. She was surrounded by relatives who were envious of Rasool Bibi’s good fortune in marrying someone who could take her out of Paharang. They would taunt her by saying her husband had already found an English bride. ‘Do you really think he is in England and thinking about you? He could have his pick of white girls, why would he want to stick with you?’ My mother listened to their insults but told herself they were jealous. Nevertheless, her children were the only ones who did not have a father in their lives. All my mother had to offer her children were letters. Navela and Sohail were confused that their father seemed to be available only in the letters that he sent. ‘Mummy, is our daddy made of paper?’ Sohail would ask.

No one thought to keep the letters, so the only clues about what my father’s life in Britain was like are in the handful of photographs from that period. One was taken in the winter of 1963. My father is wearing a loose slate-grey suit with a black tie and standing next to a vintage automobile. What is so extraordinary about the photograph is seeing my father looking so fabulously cool; the image could have been a scene from a thirties gangster flick. To my eyes he looked the same in the photograph as he did in the flesh; dapper and smart. Even when living in a shared house he still managed to look good. Another photograph shows my father by a cooker stirring a pot. There are four other men in the picture. The men’s sideburns suggest it was taken in the early seventies. They are casually dressed in brown sweaters and plain shirts. My father is wearing a tie.

Even in these photographs my father looked out of place; there are few images of him smiling. Perhaps he was tired. No one just worked standard hours; if there was overtime available in the evenings or weekends they would take it. There were occasional excursions; Shuja and Mohammed took a train into London one weekend to visit Buckingham Palace and in the summer of 1972 they went inter-railing across Europe with two other friends. There are photographs of them on a hoverboat and in Hamburg. Mohammed is not smiling. Was it guilt? The knowledge he ought not to be having a pleasant time?

My father lived in Britain for eleven years while his wife and children remained in Pakistan. During this time, he visited only three times: three weeks in 1965, eight months after his father died in 1970 and finally for another three weeks in 1973. I was conceived during the second visit. I was born in the summer of 1971 at my mother’s home in Paharang. My father was back in England, working at the Vauxhall car factory. Information took time to travel then and my father only learnt about his new son by letter some weeks later. By then I had already been named Javed by my mother. When my father read the letter he was unhappy with the name. In a hastily written response sent to my mother he told her his boy would be called Sarfraz.

Three months after I was born, we moved back to Karachi. This accounts for the language difference in our family. In Paharang the most common language was Punjabi and in Karachi it was Urdu; I grew up speaking Urdu while the rest of my family mostly spoke Punjabi. Throughout my childhood my parents would speak to everyone else in Punjabi and to me in Urdu. I can understand Punjabi but can only speak Urdu, another difference that marks me and my sister Uzma from the rest of the family.

In Karachi, during the first week of December 1971, Indian fighter jets bombed the city. Our home had no windows or doors and we could see the jets flying over our heads as they dropped bombs on oil depots and refineries. The bombing caused a power cut in the area and the lights went out in our house. My mother grabbed me in her arms and, taking Navela and Sohail with her, crouched under the stairs waiting for the raid to be over. I was six months old. After the bombing stopped she took us on to the roof of our house. The burning refineries were pumping black smoke into the sky and buildings were ablaze. When my father heard about what had happened, he became frightened and promised it would not be long before he would be able to bring us to Britain.

On 16 May 1974 Mohammed was joined in Britain by his wife and three children. Eleven years might seem like an unusually long time for a husband and wife to be apart but it was entirely normal at the time. Most of the other Pakistani families whom we knew during the seventies had similar stories. One reason why it took my father so long to bring us over was that not only was he sending money back to my mother, he was also paying for the weddings of his sisters and brothers back in Pakistan. Even as my father’s relatives were mistreating my mother by suggesting my father had remarried in England, they were also begging him to send money to fund the building of houses and family marriages. When he sent money meant for my mother, it would be intercepted by the relatives. My mother, vulnerable since her husband was so far away, was powerless.

Then my father arranged for us to come to England. Two months before she was due to fly Rasool Bibi told her mother she was leaving Pakistan. The shock of hearing this threw my grandmother into a fever which killed her just weeks before my mother left the country.

My mother arrived at the airport in Lahore with five rupees in her purse, one large suitcase, one bag of luggage and her three children. We flew on the cheapest ticket available, an Afghan Airlines flight from Lahore with a stopover in Kabul. Sohail was given the responsibility of keeping an eye on the passports and the airline tickets. It was he who handed our documents to the airline officials in Lahore, who was first as we boarded the plane. My mother had the seat by the window, I was in her lap with Navela and Sohail in the seats next to her. I wanted to run along the aisles and kept asking my mother to let me go but she did not want to lose sight of me. As soon as the engines started we all fell silent; my mother held my small hands inside hers, she was probably as nervous as I was but she did her best to calm us as the plane began to hurtle across the tarmac. We had not been in the air more than an hour when Sohail began to complain his stomach was feeling strange; my mother had to take him to the toilets where he was sick. By the time the plane landed in Kabul a few hours later we were all feeling queasy, unsettled by unfamiliar travelling and lack of food. Sohail led the way, my mother held me in one arm and grasped my sister’s hand. Unfamiliar with the procedures, we blindly followed the other passengers from the plane to the airport to the bus that delivered us to the hotel where we would be spending the night. At the hotel Sohail was separated from my mother and Navela as the males had to be kept apart from the women

but because I was so young I was allowed to remain with my mother.

The next morning we changed from the traditional clothes we wore when we had arrived at Lahore airport into what we were going to wear for London. From the suitcase my mother pulled out a pair of powder-blue trousers and matching shirt for me to put on. Sohail and Navela were dressed in bell-bottoms and flowery shirts.

We made our way to the hotel restaurant for breakfast. None of us had eaten since the airport and we were starving; I had begun to cry from hunger. Our mother picked up rolls of bread and some fruit from the serving area. As she walked back to the table where we were waiting a woman shouted out that the food was not free and insisted on payment. My mother went through her pockets and picked out the five rupees. ‘I’m sorry, auntie, but the food here costs more than that,’ the woman explained. I had been crying already that morning and when I heard the woman say we couldn’t have food I began to cry again. My mother began to feel agitated. ‘Please what can I buy for my children for five rupees? This little one is very hungry; we have not eaten since Lahore.’

The woman from the restaurant was about to reply when she was interrupted. ‘Shame on you! Can’t you see the little boy is hungry?’ It was another passenger, a middle-aged woman who had overheard the conversation. ‘Auntie, if you don’t have enough money, please let me buy you and your children something,’ she said kindly.

My mother smiled weakly and gave her thanks for her good heart. With some money from the woman and our five rupees my mother bought a packet of peanuts and some bread. It was dry and salty but it filled our stomachs.

A coach picked us up from the hotel and took us back to the airport where we boarded the plane that flew us to Paris. During the flight Sohail developed a severe case of diarrhoea and my mother had to look after him because he couldn’t stop vomiting. Tending him meant there was no time to think about her own weak condition; she had not eaten since Pakistan.

When the flight arrived into Paris there was another five-hour delay before the next connection. There was no hotel and the time was spent stretched across the seats of the departure lounge. This final stage of the journey was the shortest; we landed in London only an hour or so after taking off in Paris.

After we collected our luggage we were directed towards a medical office for a check-up. When they tested my mother, she was so weak they feared she had TB. They had to conduct further tests before they were satisfied she was not in danger. Once she was given the all clear, my mother, Navela, Sohail and me headed towards the exit.

‘And who is this little one? Where has he come from?’ my father said, picking me up and kissing me on my cheek. I was almost three. Years later my mother would tell me how all through the flight I had kept asking, ‘Are we seeing Daddy? Will my daddy be there?’ and whenever my father wanted to embarrass me he would repeat how I burst into tears the moment he held me in his arms.

I can only imagine how strange the situation must have been for both my mother and my father. For Mohammed it meant a sudden adjustment in his life from virtual bachelor to married father of three. It can’t have been easy. When he had said goodbye to my mother he had been twenty-nine and now he was forty-one.

Recently my mother admitted to me that when she saw my father at the arrivals terminal at Heathrow her first response was not pleasure but cold fear: what if this man lets me down? When she arrived in Britain my mother couldn’t speak a word of English, she had Sohail, Navela and me to think of: if my father failed us where could she go? Fortunately my father was an honourable man. Within months of landing in London we were living in our own home, a two-bedroom terraced house on Selbourne Road in Bury Park in Luton.

We did not know that Luton had such a dire reputation. We lived there because my father worked at the Vauxhall car factory which was the largest employer in the town and such a significant presence that it had its own brass band, football team and beauty pageant. The ‘Miss Spectacular’ contest was open to any female employees of Vauxhall; the evening we arrived in Luton the final heat was being held with Valerie Singleton chairing the judging panel.

My father had only managed to buy our home because a group of friends had lent him money for the deposit. Evidently they had not lent him a penny more because when we first moved into the empty house my father couldn’t afford to buy beds for us to sleep on. We slept side by side on the living-room floor on bed sheets spread out on the maroon carpet. When we eventually bought furniture it was all from salvage yards and second-hand stores, which my father visited every weekend without fail. The pressure to pay the mortgage and pay off his loans meant he worked all the overtime that was available; white colleagues would joke that Mohammed had moved into Vauxhall and was living in the factory. The more he worked the more frustrated he would be that he was not earning more money. ‘I am not a donkey,’ he would say to my mother. ‘I cannot carry the rest of you on my own. I work like a dog but I am not a donkey.’

My mother, cooking saag aloo on the gas stove and tossing hot chapattis in the air to cool them, must have felt helpless.

My mother had been in Luton less than six months when my father began taking her to textile factories in town. As a young girl when my mother’s father suddenly died she had to support her family. To earn money she made clothes for the women in her village, taking the patterned silk and handstitching it into shalwaar kameez. She could use this skill in England as dressmaking was a common means of earning money amongst newly arrived immigrants, and the situations vacant pages of the local paper often contained offers of work in locally based textile factories. My father would read the advertisements and make notes in his diary. On Saturday afternoons after he had visited the second-hand stores he would take my mother to the factories and tell whoever would listen that his wife had many years of experience making clothes and would be a very good addition to the workforce. No one wanted to give her work because she could not speak English. My father said that this was not a problem. ‘It’s good she doesn’t speak English,’ he told them. ‘It means she can spend more time working. No chance to chit chat!’

When the managers would say that was all well and good but how were they meant to teach her how to make the dresses, my father had a reply to that too: ‘Not a problem. Just tell me what she has to do, I tell her, and she does it. No problem.’

It must have been a strange experience for my mother, mutely listening as my father animatedly discussed and pleaded with a succession of whites for them to give her a chance to work. Everywhere they tried they were knocked back until finally they met one man who said that my mother could work from home.

My father bought a second-hand, black Singer sewing machine and stationed it in the living room. With the sewing machine in position the ritual that would continue throughout my childhood began. Each week a man would come with bundles of material tied up with string; there would sometimes be dozens of such bundles piled high in the living room. With the bundles would come a sample to show what the bundles had to be transformed into. For every finished dress my mother would earn something between forty-five pence and a pound. Those same dresses would then be sold in the nation’s high streets.

During the day, my father would be working at the factory, Sohail and Navela were at school and I would be alone with my mother. It was probably boredom which prompted me to start helping but, at four years of age, it became my job to untie the bundles of fabric. When my mother had completed a dress it was my responsibility to lay it flat down on the floor, one on top of another so that they could be tied into bundles of ten ready for collection. When Navela returned home from school she would join my mother at the sewing machine so that when our father came home from work and asked how many, they could give a figure that would satisfy him. After dinner the living room would be transformed into a factory production line with my mother and Navela taking turns on the sewing machine, my father and Sohail hemming and overlocking, while I would count the dresses and arrange them in bundles of ten. As I became ol

der I was given other duties: turning cotton belts inside out with a knitting needle and threading them through the loop holes of the dresses, and changing the thread on the sewing machine when Mum began working on a dress of a different colour.

No matter how hard they worked my mother and Navela never received any praise from my father, only urged to work harder. If they worked into the early hours of the morning they would make mistakes and when the man came to collect the dresses he would sorrowfully tell my father that he was unable to pay for faulty handiwork. This would throw my father into a rage.

When they were not making dresses for Marks & Spencer and British Home Stores, Navela and my mother made their own clothes. My sister would draw out an outline of a dress on tracing paper and design its own unique pattern around the neck. A shalwaar kameez gains its uniqueness from its length and how its neck and sleeves are shaped. When they went shopping in Bury Park other Pakistani women would approach them and say, ‘Sister, can you tell us who made your clothes? They are so beautiful!’ and Mum would tell them with pride that she had made them with her daughter.

‘Sister, a small request?’ they would then say. ‘Could you spare some time to make me something as beautiful?’

My mother and sister became Bury Park’s leading fashion designers and dressmakers; before they handed the finished garments to their clients Navela would try them on herself and be photographed wearing them.

With the money they earned my father bought my sister a gift: a smaller domestic sewing machine so she could sew at the same time as my mother. The last thing I would hear before I slid into sleep was the groaning of the sewing machines and the dull vibrato of the floorboards.

As a small boy the consequences of poverty were few toys and no holidays; birthdays were family only affairs where each year my mother would prepare the table with samosas, pakoras, spiced chickpeas, plates of crisps and slices of sponge cake and Navela would take the annual photograph of me or my younger sister Uzma blowing out the candles. We never celebrated Navela or Sohail’s birthdays and no one outside our family was invited.

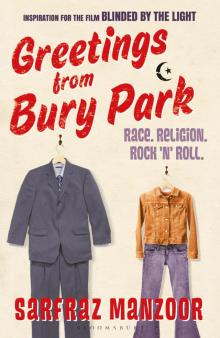

Greetings from Bury Park

Greetings from Bury Park