- Home

- Sarfraz Manzoor

Greetings from Bury Park Page 3

Greetings from Bury Park Read online

Page 3

I did not appreciate until later how frustrating it must have been for my father to not be able to give more to his children. Whether it was Sohail demanding a cassette radio player or Navela wanting more clothes or all of us hoping for a colour television the demands were continual and the finances limited. When he could he would surprise us. In the winter of 1978 I was seven years old and, thanks to ‘Mull of Kintyre’, I was obsessed with having an acoustic guitar. My father spent sixteen hard-earned pounds to buy me one. It is my happiest childhood memory, the magical sensation of wanting something badly and receiving it.

Unlike some other Pakistani men my father was not frittering his wages. His only vice was smoking. When friends visited our home at weekends they would play cards and talk about the old country while taking turns to suck deeply on the hookah. The gurgling sounded deep and mysterious. During the week he would disappear into the back yard for a cigarette, returning minutes later with the stench of the smoke still clinging to his cream kurta. Eventually, my mother’s continual nagging prompted him to give up smoking. I am pleased my father smoked; glad that there were some things he did purely for pleasure and only for himself.

* * *

The doorbell rang. It was September 1979 and we were leaving Bury Park to move into a house in Marsh Farm.

My father opened the door. ‘Salaam, Sadiq sahib,’ he said, welcoming the visitor into the hall and leading him into the living room.

‘Salaam, Manzoor sahib,’ whispered Sadiq. Mohammed Sadiq was one of my father’s oldest friends. Their friendship went back to the days when they both lived in St Albans. My father worked as a postman while Sadiq earned his living at a local asbestos factory. Sadiq didn’t work any more, the accumulation of dust particles in his throat had left him unable to speak in anything louder than a whisper. With his greying hair, pepper moustache, light-brown kurta pyjama and leather chupulls, Sadiq looked like a hundred other men you might see walking along Dunstable Road with bags of halal chicken in their arms.

‘Is a cup of tea possible?’ my father asked my mother.

‘It’s already ready,’ replied my mother.

‘Where are the little ones?’

I was eight years old and my younger sister Uzma had turned four two weeks earlier.

‘Uzma and Javed are in the garden and the other two are upstairs,’ my mother replied.

Even though my name was legally Sarfraz, at home my family continued to refer to me as Javed.

‘It was the older ones who told you to move, isn’t that right?’ asked Sadiq.

My mother walked in with a silver tray on which were two cups of steaming hot tea and a plate of egg biscuits. ‘Please,’ said my father, motioning towards the tray.

’So, why are you turning your back on us, Manzoor sahib? Has the father started obeying the children?’

‘The children kept saying they wanted to move from here,’ my father explained to Sadiq in between sips. ‘The two older ones saw the house and they have been on at me for months saying they want to live there.’

Although we lived in Bury Park my father had insisted that both Navela and Sohail attend a high school that was two bus journeys away. The local schools in Bury Park were overwhelmingly Asian but Lealands was almost entirely white. My father was convinced that this made the school better. It was while walking back from school one afternoon that Navela had seen a house for sale; this was the one that we were set to move into.

Sadiq carefully peeled the skin from the top of the tea and tipped three teaspoons of sugar into the mug. He picked up an egg biscuit and slowly and thoughtfully began nibbling. By this time Uzma and I were also in the living room but we knew better than to take a biscuit. We could only help ourselves when it was made clear that guests had eaten what they wanted. Fortunately it was also customary to put out far more than guests could possibly eat; a subtle way of indicating family prosperity.

‘That area you are moving to is very white, Manzoor sahib. How are you going to make sure the boys go to the mosque to learn the Koran? Very few Pakistanis in Marsh Farm.’

I looked at my father, hoping for permission to grab a biscuit. But he was looking at Sadiq. ‘Their mother taught Sohail and Navela at home, no reason why the little ones can’t learn the Koran at home too.’

’Yes, but you know the morals of white people, Manzoor sahib,’ Sadiq continued. ‘You don’t need me to tell you what they get up to. Keep an eye on the little ones. There won’t be any Pakistanis in their schools in Marsh Farm. Too many white people around and they will start thinking they are white too. Do what I do: take the children to Pakistan in the summer, let them see their relatives, their country. Otherwise they will become strangers to you.’

My father must have recognised what Sadiq was talking about. It was what every conversation amongst adults seemed to eventually settle on: how to try and protect the children from temptations and reinforce their Pakistani identity. They must have felt they were trying to turn back the tide of progress before it rose to destroy and tear apart their families.

But it was this tide of progress that had carried my father from Pakistan to England. It was this impulse towards improvement that had compelled him to be away from his wife and children. My father was a man perpetually on the move, driven by a relentless desire towards something and somewhere better. His friends frustrated him because they reminded him of who he was, and not what he wanted to be. Most of his friends were men who were not able to talk about the things he was interested in. What they had in common was the old country. When they discussed General Zia or the death of Bhutto they felt connected to each other and their homeland. The only other thing they had in common was children. ‘What is Sarfraz going to be when he becomes a man?’ one would ask my father.

’What do you mean, he is a man already!’ someone else would add.

‘My son will be a doctor,’ a third would boast. Back then that claim had yet to harden into cliché.

Beyond the realm of children and Pakistan the conversation stumbled; these were not men truly interested in how each other was doing; they only wanted to demonstrate to the rest the extent of their success. My father wanted to discuss politics with politicians, business with industrialists. Instead he was having tea with uneducated factory workers, his awkwardness betraying his frustration at his own unfulfilled existence.

What drives a man to leave his country, to accept demeaning work for more than a decade so that he can bring his family from Pakistan to join him? Why didn’t he just find an English girl like many other Pakistani men had? Was it not tempting to forget his Pakistani family and start anew? What was remarkable about my father was how these temptations were unthinkable to him; his moral framework was underpinned by family, responsibility and pride. Those values were who he was, they shaped how he raised his children, they shaped who we became, and yet they were the very values I ridiculed. I condemned him for being tough without appreciating that if he had been softer we would have remained in Pakistan. What made my father different was that he was consumed with a passion for self-improvement. It is staggering how someone who came to this country in the early sixties, who was never able to fulfil his own potential, and who met with racism on a daily basis, was able to inject into his children – or his sons at least – a sense that the entire world was available to them if we studied hard and worked harder. ‘The only way whites will give you a job is if you are twice as good as them and work four times as hard,’ he would tell me. Families could progress but only if the children recognised and understood their duties and obligations. This was the most important thing I learned as a small child. My father had brought us to this country and in his eyes it was our duty to work hard, not complain, not expect too much and, most importantly, not let him down.

While, like all parents, my father wanted to be proud of us, it was crucial we did not embarrass him or the family. What ‘the community’ thought took on an absurdly high significance; we had to act as if our entire lives were bei

ng recorded for the critical approval of this community. I found this obsession with keeping up appearances infuriating. ‘Who cares what people think?’ was a common unanswered question.

But Mohammed Manzoor drew his strength from his community, and also from his pride. In the sixties he worked in a lightbulb factory in Hertfordshire. At lunchtime he would eat his chapattis and the white workers would laugh and point at him, saying, ‘That stupid Paki is eating brown paper!’ How do you fight the feeling that everyone hates you? That for all your dreams and desires you will never achieve your own potential? By believing completely in your abilities and having pride in what you are. That was my father.

In the early eighties my father was promoted from the production line and became an inspector at the Vauxhall car factory. He was required to wear a white overcoat, watch what the factory workers were doing and point out any mistakes that might have been made. It was a job almost tailor-made for his talents because the irony was that while my father preached the sermon of hard work he himself was actually rather workshy.

The ways he got out of work were fairly comical. For all his sternness there was another side to my father; it was a side that my mother and my sisters were best at extracting. When he knew he’d been rumbled, like when he took more chapattis when my mother had already said he’d eaten enough, he would cover his eyes with his hands and peek through the parted fingers like a naughty boy. ‘Take it easy with my curry,’ my mother would joke, ‘we don’t want you becoming fat, do we?’ Then my father would stand up and start running on the spot, saying, ‘See! See how fit I am!’

When it came to work around the house my father always assumed what he called an ‘executive supervisor’ role. ‘Someone needs to be monitoring what you are all doing,’ he would say, trying to suppress a grin. ‘Supervising is the most important job.’

While my mother washed and cut up chicken and I chopped onions’ wearing my swimming goggles to stop the tears streaming down my face, my father would be in the living room roaring with laughter at the Laurel and Hardy film on television. (When he was being especially playful he liked to give a little Oliver Hardy wave to my mother.)

‘How did you manage to live all these years in England and not cook?’ my mother would ask innocently. ‘Fish and chips every night was it?’

’Daddy can cook,’ I would say, ‘I’ve seen photographs of him in the kitchen.’

‘If your daddy ever sets foot in this kitchen then I swear to Allah that I too will take a photograph,’ Mum would retort.

‘So, don’t you have anything to say for yourself?’ Navela would ask him playfully.

‘What are you talking about? The most important part of cooking is not the chopping and the slicing. Anyone can do that! The most important part of cooking is the recipe. Ask your mother where the recipe came from. Go on, ask her.’

It was true – the roast chicken that we cooked was based on a recipe that my father had passed to my mother. It was how he had cooked chicken in the sixties.

My father loved gardening. For us the garden was not only a place of beauty but a source of food. At Bury Farm our garden was a slab of concrete, but when we moved to Marsh Farm my mother was able to grow potatoes, onions and mint leaves, which she ground into chutney. There were also flowers; my parents would choose which colour flowers they wanted to plant and my father would buy the seeds. It was very important to my father that we maintain a neat and tidy garden, which was why mowing the lawn was a significant responsibility. Long grass – like long hair – suggested a certain moral laxity which invited the ridicule of others. When my father pointed out that the neighbours had recently cut their grass while ours was looking unkempt he was not merely making an observation. All his obsessions with pride and keeping up appearances were apparent in his compulsive desire to ensure that our garden lawns were kept neat. On Saturdays my job was to mow the grass in the front and back gardens. While I was busy operating the lawnmower, my mother would sit at the edge of the lawn trimming with a pair of scissors the wisps of grass that the lawnmower could not reach. When that had been done it was then Uzma’s role to collect the cut grass and dump it in the dustbin. After that finally my father would emerge, take out a plastic rake and gently rake over the freshly mowed grass, making sure that none remained. This usually took no time at all but once he had finished he would make a great play of what he had done. ‘See how neat it now looks?’ he would say to us.

‘Listen to him!’ my mother would say, laughing. ‘Spends two minutes going over the garden and tries to pretend it’s all his work! No shame! No shame at all!’

Dad would be trying to suppress his own laughter. ‘Why are you saying such a thing? You know that in any job there have to be workers and there has to be management. My role is to be a supervisor.’

‘Dad?’

‘Yes, son.’

‘Does supervise mean getting everybody else to do the work and then claiming credit for it afterwards?’

By now we would all be laughing as we bundled back into the living room to settle in front of the television for the weekly ritual of watching Dickie Davies and the Saturday afternoon wrestling.

The wrestling was an obsession for my father. All activity in the household on Saturdays was planned around it; if the family were out shopping they knew to be home by four thirty. Why wrestling was so important was never explained. My father was also a huge boxing fan and I had grown up watching Muhammad Ali fight; I can understand his love of Ali but why Giant Haystacks and Big Daddy exerted such influence I do not know. And yet, the communal ritual of watching the wrestling featured regularly throughout my childhood.

When we watched television we could push the pause button on our lives while other lives played out before us. During the IRA hunger strikes I rushed into my parents’ room each morning to ask my father if Bobby Sands was still alive; I followed the trial of the Gang of Four in China and the Yorkshire Ripper in Britain and I looked forward to Question Time just as much as Knight Rider. In the evenings, after my parents had gone to bed and Navela and I had watched the late movie together, my father would call me up to his room to discuss politics and listen as if he really cared what I made of Labour’s chances in the general election. Years later my mother told me that my father really enjoyed those conversations, that talking to me about politics made him feel that we had something in common.

My father was obsessed with tidiness. Apparently he had even been like that many years earlier when he had lived with a dozen other men in a shared house. His friends from that time would speak of how, even if the entire house was a chaos of mess, Mohammed Manzoor’s area would be spotless and he’d complain to the others about the state of the house. This obsession meant that he asked us to go to extreme lengths in order to have a tidy house. For example, where the sewing machines were used by my mother and sister the carpet would be messy with rags of excess fabric and tiny pieces of cotton thread. My father would ask my sister and me to clean the carpets by hand. The vacuum cleaner could not, he told us, be expected to clean the carpet thoroughly. Far better for us to get on our hands and knees and pick up each thread and rag individually. We didn’t find this peculiar, for us it was just another game to play. We would choose opposing sides of the room and compete over who could collect the most strands; Uzma used an old hairbrush to exfoliate the room. When we had finished we would each offer up our piles of threads, fluff, pins and buttons to our father for inspection. But there was never a sense of accomplishment from this task, we always felt like we had let him down again; by failing to pick up every single strand from the carpet we had merely confirmed how we could not be trusted to do even the simplest task.

If it wasn’t hand cleaning the carpet there were countless other ways to try and keep me occupied. The answer you could never give to the question ‘what are you doing?’ was ‘nothing’; saying that I was reading a book was almost as bad. When I remember my teenage years the one thing I wanted to do most was just that: nothing.

/>

For a man so outwardly proud my father seemed remarkably relaxed about allowing his wife to work and his children to wear second-hand clothes. The jumble sales were held in the assembly halls of the Maidenhall school and my junior school in Marsh Farm. I would look forward to these with the same passion that later would be reserved for Bruce Springsteen concerts. Jumble sales and libraries were where I satisfied my desire for stories and stimulation; there were no new books in our home but dozens of second-hand issues of Reader’s Digest which I would devour in the evenings before I went to sleep. My mother and I would stand at the school gates thirty minutes before they opened and as soon as the teacher admitted us through I would dash into the central hall where there would be tables filled with piles of clothes, books and toys. My mother would rifle through the clothes picking out trousers, shirts and jumpers; she could make clothes for Navela and Uzma but I had to manage with my brother’s hand-me-downs and whatever she found in the piles.

My mother only bought me shoes that were much too big for me, which meant that throughout my years in junior and high school I had to wear two pairs of socks to ensure my feet did not helplessly slide around inside my shoes. Once she bought me a pair that was so big I had to fill the toes with screwed-up newspaper; at school I was briefly called ‘Ronald McDonald’.

As embarrassing as wearing outsized shoes and second-hand clothes was for a young boy, I was not especially upset about it; my father had done an excellent job of hammering down his children’s expectations of him while at the same time maintaining very high expectations of us. Many years later when I was living away from home, friends told me that their parents had given them something they called ‘unconditional love’. But Asian parents of my father’s generation knew nothing of unconditional love, a sitar came with fewer strings attached.

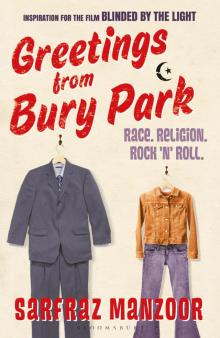

Greetings from Bury Park

Greetings from Bury Park