- Home

- Sarfraz Manzoor

Greetings from Bury Park Page 4

Greetings from Bury Park Read online

Page 4

* * *

My best friend at school was Scott McKenzie, a freckle-faced, chestnut-haired lad who lived only minutes from my home. Ours was a somewhat unlikely friendship. I liked reading books and Scott was a star in the school football team; I was painfully shy around girls while Scott was the boy all the girls fancied; and while I was still sharing a bedroom with my brother, Scott’s bedroom was an Aladdin’s cave of treasures filled with posters of Bryan Robson and Steve Coppell, a dartboard and record player. Since he lived so close I was allowed to visit Scott’s home in the evening. His mother would ask about his homework and Scott would be jealous when I told him that my father never asked such questions. ‘You’re so lucky,’ he would say. ‘My dad won’t let me out of the house unless I’ve finished it.’ My father cared nothing for homework, what mattered was that I passed my exams.

In the evenings as I massaged his feet, my father would be reading the newspaper while my mother would be in bed beside him. Their bedroom smelled of incense. I would sit at the bottom of the bed, slowly and firmly squeezing his feet and calves, and then he’d begin. ‘So, how old are you now?’

It seemed to be a rhetorical question but once I found a small notebook into which he had written the names and birthdays of all his children. ‘Twelve,’ I’d reply.

‘Twelve? Practically a man then. Do you know what I was doing when I was twelve? I was looking after my sick father and my sisters. I would go to school and then work in the evenings so that my family had food to eat.’

I would listen while pressing the soles of his feet, rubbing my fingers over the rough corns that scarred his toes. His feet were caked with so much thick dead skin that I would sometimes need to shave it off with a razor blade. It was a curiously satisfying experience watching the shavings peel off his feet.

‘So, do you know what you want to do when you leave school?’

‘No, not really, haven’t thought about it.’

‘Haven’t thought about it! What sort of answer is that? Look at your mother. Even before you can remember she has been looking after you. You have no idea what she has been through, the sacrifices that she has made. Now it is your time to make sacrifices. Parents do their job so that the children will do their job in later life.’

Every meaningful conversation during my childhood was a variant on that theme and they could all be summarised into one statement: do not let me down. Do not forget the sacrifices I made to come to this country, to bring you here. Do not forget where you come from and who you are. Do not forget us. It was a huge burden to place on a young boy’s shoulders. But I now understand him better. He was, I think, embarrassed by working at Vauxhall. He wanted me to say to him that I would do him proud and not give him cause to be ashamed. When I heard him speak like that I felt afraid of growing up, scared of the consequences of letting him down.

I was fifteen years old when, in the autumn of 1986, my father was made redundant from the Vauxhall car factory. When I learnt that my father would imminently be unemployed I, as a typical self-absorbed teenager, only viewed it from my perspective. With my father out of work it meant money would be even tighter and I would be under greater pressure to find holiday work. I assumed this meant he would be at home all day. There would be no escape.

I failed to see that, for my father, the concept of being unemployed was deeply shameful. He was someone who believed with almost messianic passion in the very idea of work; it was not something he was willing to sacrifice merely because he did not have a job. Which was why, even after he was made redundant and even when he had nowhere specific to go, my father would wake at seven and immediately get dressed. He would then read the newspaper at his desk, a square table we had bought from a second-hand furniture store.

To judge from the mail, my father had no friends. The only letters were the very occasional aerogramme from Pakistan, but mostly it was bills and bank statements and annual reports from companies that my father had bought shares in. Years before the privatisation of the nationalised industries created millions of shareholders my father was buying and selling on the stock market. Despite his constant protestations that our family had no money, he seemed to find the cash to trade in stocks and shares. My father did not make any money from his trading but that might have been because he had very little money to invest. Every few days reports would arrive from oil-drilling companies based in Australia, chemical conglomerates and pharmaceutical businesses. They did not make for fascinating reading, filled as they were with daunting graphs and indecipherable pie charts and statements about ‘extraordinary general meetings’. There would also be guides to buying and selling penny shares and updates on the companies to watch.

Once he had absorbed the daily information my father would call Arthur. Arthur Bryant was my father’s stockbroker, someone he had known since we lived in Bury Park. I imagined him as Charlie in Charlie’s Angels since he only ever appeared to exist on the other end of the telephone. After my father was made redundant he became convinced that there were great fortunes to be made in the stock market, if you had the initial outlay. ‘Money makes money,’ he would tell us. ‘If someone were to give me one hundred thousand pounds I could turn it into a million, with the knowledge I have. But you need to have the money to invest.’ That was where my mother and Navela came in, working on the sewing machines while my father chatted to Arthur. Every conversation started with the same words: ‘Good morning, Arthur, how’s the market today?’

I never heard Arthur’s assessment but I would see my father making notes in his diary before issuing instructions about buying five hundred of one company and selling three hundred of another.

With the paper read and the shares traded, my father would say goodbye to my mother, appearing for all the world as if he was leaving for work. In fact the entire day would be spent with his friends. These visits were not entirely social. My father was the first port of call for any Pakistani who was interested in buying a house but was ignorant of how to secure a mortgage; he spoke English well and knew how to deal with bank managers. He didn’t charge a fee for his time. Later, when men would call on him to help with their passport and visa problems, he would spend afternoons filling in forms so that they could bring their wives to England. He did not charge for that either. At the time I did not know what he was doing in those afternoons that he disappeared; I was simply grateful he was not at home.

After his redundancy my father could not claim that he was the main breadwinner for the family; my mother and Navela were earning the family income with their dressmaking. No one dared to make the obvious observation to him that he did not have the authority to lay down the law if he was not bringing in the money. We continued to behave as if nothing had changed.

While I lived at home it did not occur to me that my father might have felt embarrassed and emasculated after losing his job. Maybe he felt disappointed in himself, which was why it became so imperative that we should not disappoint him. But the only thing I felt at the time was frustration. Too absorbed in myself, I did not notice that when the local paper arrived every Thursday my father would scan the situations vacant for work; sometimes he would ring to enquire further but not once did he get an interview. When my father would speak to his bank manager or the local estate agents he would joke with them, ‘I know as much as you do, you should give me a job. Consultant. I could do that for you.’ He was not actually joking, of course, but I would hear laughter coming from the other end of the telephone. The very idea.

My father represented the past; that was what he talked about, what he celebrated and what he wanted to preserve. My eyes were fixed firmly on the future, a life far from Luton and all its limitations. We were so different and yet anyone who saw us together could see which side of the family my features were from: the high forehead, the full lips, the fleshy earlobes and, most telling, the coarse curls of my hair. My hair was the most visible reminder of my father; I hated my hair.

My brother and sisters all had straight hai

r inherited from my mother; hair that could be grown long, combed easily, hair that could fall in front of their eyes or be tossed around by the wind. My mother used to tease me and say I had steel wool on my head; Navela would try to persuade me that I was an eight-year-old spitting image of Paul Michael Glaser in Starsky and Hutch. As a teenage boy the limitations of what could be done with my hair were a source of constant irritation. I wanted hair that would grow long, hair that I could whip in the air as I sang along to ‘Living on a Prayer’ or ‘The Final Countdown’, hair that would keep falling in front of my eyes so that I’d need to flick it back in a sexy, possibly seductive, way.

My older sister cut our hair at home. The hallway was the temporary barbershop. We would sit facing the mirror that hung from the wall, an old bed sheet draped over us and tucked into our collar. She used the same scissors that my mother would use for cutting fabric before stitching dresses together. I was a recalcitrant client; I resented not being able to go to an actual barber. ‘Don’t you realise white people pay to have hair like yours?’ my father would ask me. ‘Those mad fools spend money to have hair that you have for free!’

Navela also was responsible for cutting and dyeing my father’s hair. Once my father’s hair had been shorn Navela would pour the hair dye into an old saucer and stir the tar-like goop before dabbing it onto a small square of sponge. She would then brush my father’s temples with the dyed sponge until his hair shone like a vinyl record.

By seventeen my desperation to leave Luton for somewhere else was only marginally more intense than my resentment at my father for having held me back. My teenage life had been nothing more than a failed checklist. Mostly disappointment remained safely buried, only expressed through listening to songs like Janis Ian’s ‘At Seventeen’. I was too scared to get angry in front of my father and I was riddled with guilt at the prospect of blaming him for anything. Who was I to complain? When he and my mother had suffered and endured so much. That guilt, the feeling that I ought not to feel like I deserved any better, meant that I never went through that teenage time of rebellion when you think that your parents know nothing and when you tell them that. I was too aware of the price that had been paid to give me the luxury of being able to complain. My frustrations remained suppressed.

At college I discovered Bruce Springsteen. In his music I found a new way to understand my relationship with my father. In ‘Independence Day’ Springsteen sings in the character of a son speaking to his father. Springsteen’s father had been a bus driver and he had never approved of his son’s rock and roll. Springsteen described his father as taciturn and unemotional. I identified. ‘Independence Day’ is the story of a son trying to tell his father that he is now his own man and that the old rules don’t apply any more. When Springsteen sings it he doesn’t sing with anger, he is not taking any pleasure when he tells his dad that ‘they ain’t gonna do to me what I watched them do to you’. What most impressed me about ‘Independence Day’ was the empathy that Springsteen had for his father. It isn’t that he is angry with his father for having different values and believing in different things. ‘There’s nothing we can say can change anything now,’ he sings, ‘because there’s just different people coming down here now, and they see things in different ways and soon everything we’ve known will just be swept away.’ Those lines made me understand the fear that drove my father and men like him: that all the things they had experienced, the values they had tried to pass on to their children were all for nothing. Until I heard ‘Independence Day’ I’m not sure this fear was something I had even bothered to consider. That was what made the song so important; it opened my mind to the pain that my father was feeling and it made me think of what he might have been feeling.

At the end of the song Springsteen tries to explain that in wanting his freedom he is only trying to secure what is rightfully his, not deliberately trying to hurt his father. ‘Papa, now I know the things you wanted that you could not say,’ he sings, ‘but won’t you just say goodbye, it’s independence day, I swear I never meant to take those things away.’ That last line always blew me away. Bruce was saying that it was not selfishness or malice that was driving him; it was just the order of things, this was what happened with the passing of generations.

The realisation that the tension between my father and me was not unique, that it was something as old as time, something that Springsteen also experienced, was a huge comfort. I was not alone. When my father was driving me insane, I would sing ‘Independence Day’ to myself and imagine I had the courage to say those words to him. I never did.

In the autumn of 1989 I left Luton to start university in Manchester. My brother had graduated from Nottingham the previous year and it was always assumed and expected that I would follow him to university. For my parents attending university was a sign of success and status; for me it was a means of getting the hell away from them. When I finished university I remained in Manchester for another three years, returning to Luton only because of guilt, duty and Bruce Springsteen. On the day that I graduated from university Springsteen was playing Wembley Arena; I skipped my graduation day and went to the concert. When my father later asked when my graduation day was I told him that it had been and gone.

I did not know it at the time but while I was growing up away from home my father was changing. When I had lived with him, he had mouthed the right words about religion but had never shown much interest in exploring it. After the Eid visit to the mosque my father would mock the imams, saying, ‘They are all thieves. They collect cash and say it’s on behalf of the mosque but a few months later the imam gets an extension on his house!’

But while I had been going to see Oasis at the Hacienda my father had developed a more profound understanding of his faith. He dressed less in his beloved shirts and ties and move in the traditional kurta pyjama. When I rang home from my Manchester home to speak to the family my mother would tell me that he was at the mosque. When I asked why, she would explain that he had said that he found it soothing and inspiring to discuss religion with the imams. He even had begun to set aside an hour a day to read the Koran.

In his later years Mohammed softened. Living away from home I did not notice the way that the others did. He discussed making a pilgrimage to Mecca with my mother. Seventeen-year-old Uzma was astonished when he had taken her to PJ Shoes and bought her a pair of knee-length boots. I had been shocked when he had not raised any objections to my going to see Bruce Springsteen six nights running at Wembley Arena. At the time I assumed that we had worn him down. Now I think that he was genuinely becoming more at ease with his children. When we spoke he was less argumentative and more interested in hearing what I thought. He seemed less angry, less bitter at my life choices. Perhaps he had given up on me or perhaps his faith was encouraging him to try fresh ways of reaching out to me. Perhaps he had even started to believe in me. I didn’t think that at the time, only later.

Knowing now that my father was not the authoritarian dictator I had constructed in my imagination, I understand better his reaction when, in early 1993, he did not explode with anger when I came home with a new hairstyle. I did not see my dreadlocks as blatant rebellion; it was not done to deliberately outrage my father but I was still wary of his reaction. When I returned home with my new dreadlocks I kept a large woollen hat on my head. ‘Your son has had a haircut,’ my mother said as I edged past them.

I rested my acoustic guitar by the side of the wall and faced my father. ‘So, take your hat off, let me see this new hairstyle.’

I smiled, pulled off my hat and shook my head until the dreadlocks were freed and flailing.

‘Is that another hat?’ he asked, not yet betraying any reaction.

‘No, this is my hair.’

‘This is your hair?’

‘Yes.’

‘All this is your hair?’

‘No, some is extensions that have been weaved in.’

‘Don’t you understand? Your son wants to be Jamaican,’ my mother sai

d in a tone of mock patience. ‘He doesn’t want to be Pakistani, he is not a Muslim. He wants to be black. Congratulations: two Pakistanis have given birth to a Jamaican son. Have you brought some ludoos to celebrate this special day?’

My father did not fly into a rage. Not then and not later. He was only disappointed and embarrassed. When Sadiq came to visit us I would be banished upstairs and Uzma would deliver my curry and chapattis to my bedroom. While I understood that it must have been strange to see their son looking so alien I couldn’t see at the time why it should be the cause of such disappointment. But I think I understand now. For my father my hairstyle was emblematic of something far deeper; in rejecting my coarse curls I was rejecting him and everything that he stood for.

Two weeks after the Elizabeth Wurtzel interview I received a phone call from my brother telling me my father had been taken to hospital. It was the last Sunday of May and I was watching New York, New York on television at my flat in Manchester. ‘You need to come to Luton,’ he said.

I did not have a car and there were no trains travelling south at that hour. It was past midnight but in desperation I called my friend Paul. He had friends round, but once I told him the reason I was calling he immediately offered to drive me to Luton. Thirty minutes later Paul was outside my home in West Didsbury with two of his friends. In the small hours of the morning we set off for Luton and Dunstable Hospital.

I was told later what had happened. My father had been in his bedroom reading the paper. Harold Wilson had died the week before and his death had put my father into a reflective mood. He had been reading about him when from nowhere he had found himself burping uncontrollably. The burps had become more frequent and more painful. My mother had suggested a glass of warm milk but it had not improved the situation. An ambulance was called. He had struggled downstairs. Uzma and Sohail were telling him not to worry but they could see he was fading. He was glistening with sweat. The ambulance had not yet arrived. My mother was saying, don’t worry, the ambulance is coming. My father had tears in his eyes. My mother would later say she knew why he was crying. He was crying because he knew he was leaving his wife to fend for herself, just like she had done for so long while he had been in England and she had been in Pakistan. My mother always said that my father was not crying because he feared death but because he feared for the lives of those he left behind. His family.

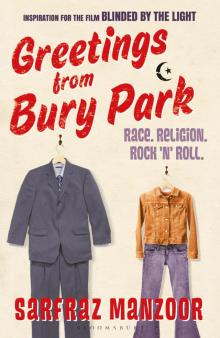

Greetings from Bury Park

Greetings from Bury Park